“Je suis un homme comme les autres” (Golaud)

22 August 2012 marks the 150th birthday of composer Claude Debussy (1862-1918) and on this day I’m going to listen – as I did so many times in my distant past – from start to finish to his opera Pelléas et Mélisande. Among the many great works of the french composer, Pelléas et Mélisande ranks as his greatest achievement. Whereas for many classical music lovers the summit of western classical music is represented by either Bach’s Matthew Passion or Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, for me (and for many others) it’s Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. Debussy started working on Pelléas et Melisande, his only completed opera, in September 1893 and almost ten years later, on 30 April 1902, this milestone in the history of western classical music premiered at the Opéra Comique in Paris.

Soprano Mary Garden, who sang in 1902 the first Mélisande at the world premiere in Paris

Pelléas et Mélisande is commonly regarded as the work that marks the onset of twentieth century modern music. The opera is based on a play by famous Belgian symbolist writer Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949). Maeterlinck turned out to be the ideal librettist for the opera Debussy had in mind to write. When once asked (before he started working on ‘Pelléas’) what poet would suit his needs, Debussy replied: “One who only hints at what is to be said. That ideal would be two associated dreams. No place, nor time. No big scene. (..) No discussion or arguments between the characters whom I see at the mercy of life or destiny.” *

The symbolist and dreamy character of Maeterlinck’s ‘Pelléas et Mélisande’ also proved to be the ideal vehicle for Debussy to juxtapose with the ideals of naturalism, for which he felt little sympathy. Debussy: “The drama of Pelléas – which, despite its atmosphere of dreams, contains much more humanity than so-called real-life documents – seemed to suit my intention admirably. It has an evocative language whose sensitivity could find its extension in music and in orchestral setting.” *

I borrow from Wikipedia to share in a nutshell a few other important notions about Debussy’s operatic masterpiece:

“Pelléas reveals Debussy’s deeply ambivalent attitude to the works of the German composer Richard Wagner” and according to musicologist Donald Grout “it is customary, and in the main correct, to regard Pelléas et Mélisande as a monument to French operatic reaction to Wagner.”

Wikipedia continues: “Debussy strove to avoid excessive Wagnerian influence on Pelléas from the start, nevertheless he took several features from Wagner, including the use of leitmotifs and the continuous use of the orchestra. But Debussy’s musical writing is completely different from Wagner. In Grout’s words, “In most places the music is no more than an iridescent veil covering the text.”

One of my favourite recordings: Ansermet-L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande-Spoorenberg-London-Maurane

“The emphasis is on quietness, subtlety and allowing the words of the libretto to be heard; there are only four fortissimos in the entire score. Debussy’s use of declamation is un-Wagnerian as he felt Wagnerian melody was unsuited to the French language. Instead, he stays close to the rhythms of natural speech. Like Tristan the subject of Pelléas is a love triangle set in a vaguely Medieval world. Unlike the protagonists of Tristan, the characters rarely seem to understand or be able to articulate their own feelings. The deliberate vagueness of the story is paralleled by the elusiveness of Debussy’s music.” So far Wikipedia.

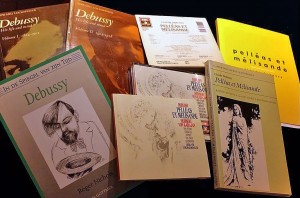

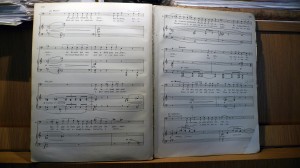

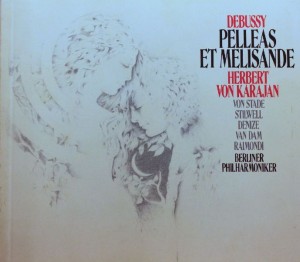

Pelléas et Mélisande is Debussy’s unparalleled masterpiece and it’s really a great joy for me to listen on the composer’s special anniversary to my most favourite ‘Pelléas’-recording, from which I embedded a segment right above here and of which I share here right below a picture. My way of celebrating the 150th birthday of the french master couldn’t be more rewarding! 🙂

The recording that’s most dear to me… a stunning achievement

* Source:

Nichols, Roger & Richard Langham Smith (1989) Claude Debussy: Pelléas et Mélisande. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.